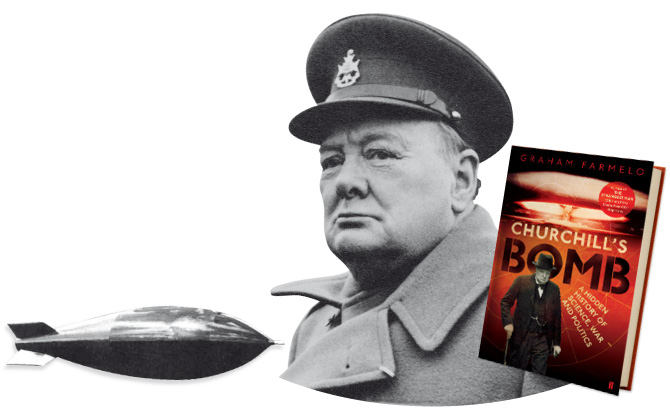

Churchill’s Bomb

A hidden story of science, politics and war

Winston Churchill was a nuclear visionary, repeatedly warning before World War II that the nuclear age was imminent. Early in WWII, physicists in Britain showed that the Bomb could almost certainly be built. Prime Minister Churchill paid only fitful interest in the speculative weapon and the initiative soon passed to the US, which had the vast resources needed to realise the venture. British scientists played only a minor role in it. Churchill dismissed warnings from the Danish physicist Niels Bohr that Anglo-American nuclear policy would lead to an arms race. After the war, the US government declined to honour a personal agreement between Franklin Roosevelt and Churchill to share their countries’ nuclear research. After Churchill returned to power in 1951, during the Cold War, he became the first British leader to have nuclear weapons, and also commissioned the H-bomb. Appalled by the prospect of thermonuclear war, he ended his political career as pioneer of détente.

Eight themes of Churchill's Bomb

1. ‘A scientist who missed his vocation’

Churchill was interested in basic science – in 1926, he was captivated by atomic physics and chaired a talk seven years later on the epoch-making nuclear discoveries made at Ernest Rutherford’s Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge.

‘All the qualities … of the scientist are manifest in him. The readiness to face realities, even though they contradict a favourite hypothesis; the recognition that theories are made to fit facts, not facts to fit the theories; the interest in phenomena and the desire to explore them, and above all the underlying conviction that the world is not just a jumble of events but that there must be some higher unity.’Lindemann talking about Winston Churchill, 15 March 1933

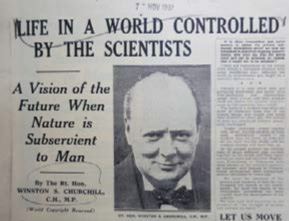

2. Nuclear visionary

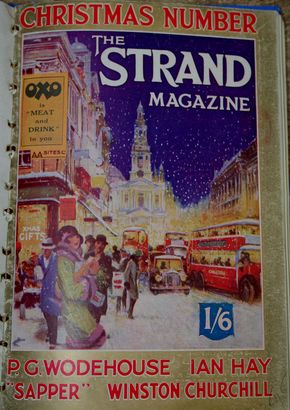

As a journalist in the 1920s and 1930s, Churchill wrote several widely-read articles speculating on the possibility of nuclear weapons and the prospect of nuclear power.

‘There is no question among scientists that this gigantic source of energy exists. What is lacking is the match to set the bonfire alight … The scientists are looking for this.’ Churchill on nuclear energy (1931)’Churchill on nuclear energy (1931)

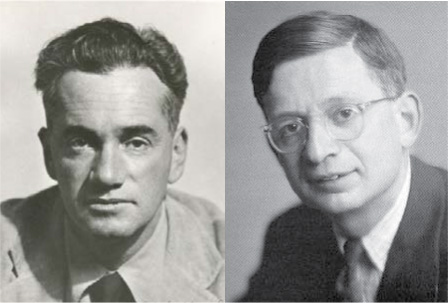

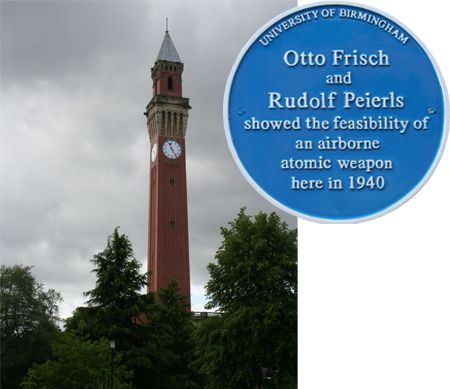

3. British first to see how to make the bomb

Shortly before Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940, two ‘enemy aliens’ at Birmingham University – Otto Frisch and Rudi Peierls – the first understood how to make a nuclear weapon. British physicists developed their ideas, which were later fully realized in the Manhattan Project.

‘As a weapon, the super-bomb would be practically irresistible. There is no material structure that could be expected to resist the force of the explosion.’Frisch-Peierls memorandum, March 1940

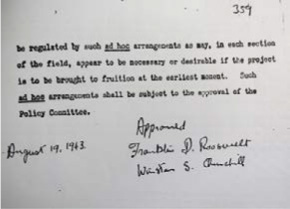

4. Churchill’s nuclear deal with FDR

Confronted with American attempts to shut down nuclear collaboration, in August 1943 Churchill signed a secret agreement with President Roosevelt. This enabled British scientists to re-engage with the Manhattan Project, and cemented an Anglo-American partnership. The deal fell apart after the War.

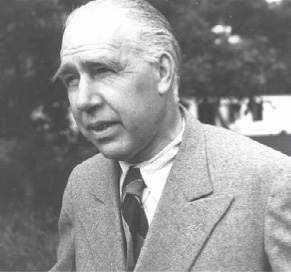

5. Bohr fails to impress Churchill

In May 1944, the great Danish nuclear physicist Bohr met Churchill and warned him of the dangers of a post-War arms race. The meeting was a disaster. Bohr had a similarly fruitless meeting with FDR. Both leaders wanted nothing to do with Bohr’s ideas.

‘He scolded us like two schoolboys’ – Niels Bohr on Churchill, after meeting him and Lindemann

6. Churchill – britain’s first nuclear prime minister

Thanks to William Penney – ‘the British Oppenheimer’ – Churchill presided over the first detonation of a British nuclear bomb in 1952. He then promoptly commissioned the H-bomb despite terrified by the prospect of thermonuclear warfare.

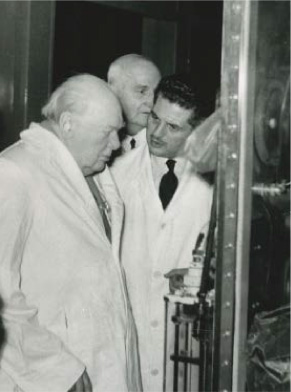

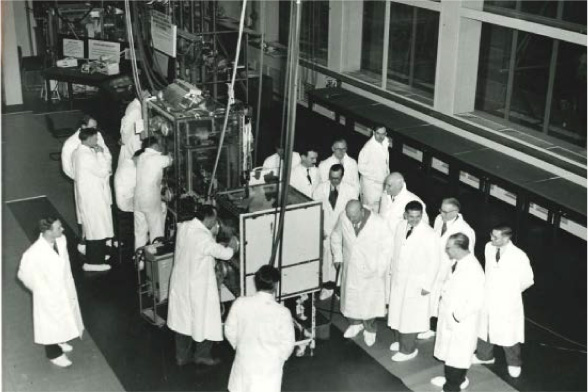

7. Octogenarian and nuclear experimenter

After leaving office, Churchill remained interested in the British nuclear programme. In his early eighties, during a visit to the British government’s nuclear research centre, he participated in an experiment to scatter neutrons.

8. Churchill’s legacy to science and technology

In the mid-1950s, Churchill decided to set up a new institution that would increase the number and the quality of Britain’s science and engineering graduates. The project became the building of Churchill College, Cambridge, whose first master was the nuclear pioneer John Cockcroft, one of Rutherford’s students.

to Top