Remembering Harry Kroto

The chemist Harry Kroto, co-discoverer of buckminsterfullerene, died in East Sussex on 30 April and his funeral took place on 19 May. Graham knew Harry well, and remembers fondly a fine chemist, an inspirational communicator, and a good friend.

Harry was born the son of refugees from Nazi Germany who settled after the war in Bolton Lancashire. He was fortunate to attend a remarkable school. Among his classmates, were three boys who also went on to achieve international fame: the educationalist David Hargreaves, the historian Norman Davies and the actor Ian McKellen.

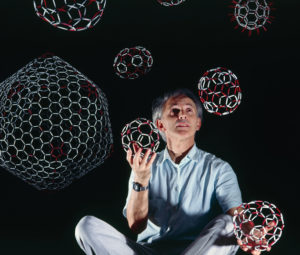

I still remember my first meeting with Harry, in late November 1996. It took place in a small office in the Science Museum, London, where about an hour before he was to give the after-dinner speech at a conference on the challenges of presenting contemporary science and technology in museums. We had invited him only days after the announcement that he and two other chemists had won the Nobel Prize for the discovery of buckminsterfullerenes, ‘spherical’ carbon molecules. When he arrived at the Museum, he was already exhausted after all the post-announcement activity but he gave a barn-storming speech, insisting that we break with tradition and enable him to talk with the aid of his viewgraphs.

In that first chat, all Harry’s qualities shone through. He was friendly, unassuming and direct, without the slightest trace of pomposity. Most striking for me, however, was that he was both deadly serious about both science and art. Even in that first meeting, when he was obviously bursting with pride about having won the Nobel, he told me that he would have been just as happy to have been an artist as he was to be a scientist. I have always thought it wonderful that fate gave him the opportunity to use his talents as a spectroscopic chemist in combination with his feel for geometry when he made his greatest discovery.

I asked him how he had found time to give this talk in his hectic schedule, shortly before he had to leave for Stockholm to pick up the prize. ‘Because the conference is funded by the European Union’, he said. It turned out that he was a devout European – just as he was a ‘devout atheist’ – and we later talked for hours about Norman Davies’ wonderful Europe: a history.

I was at that time directing the Science Box series of contemporary-science exhibitions at the Science Museum, and Harry was eager that buckminsterfulleres (buckyballs for short) should be the topic of one of them. This was easy to arrange, and he was especially keen that his colleagues at the University of Sussex were closely involved – he was not one to hog the limelight, though he loved to ‘show off on stage’, as he put it (‘God, I’m good’, he once joked after seeing himself on video performing to a crowd of a thousand school students.) He opened the exhibition in May 1998, winning a great deal of press attention. Directly after the opening ceremony, he was one of the speaker in an art-science discussion that also featured the visionary architect Chris Wise and the art historian Martin Kemp. This was one of most illuminating conversations of the interplay between architecture and chemistry I have ever heard, with Harry showing himself to be an authentic expert on the work of the American architect Buckminster Fuller.

Harry and I subsequently kept in touch occasionally, exchanging notes on the latest news about science, science communication and the arts. We had some disagreements, especially when he denounced colleagues who did business with any organisation that anything to do with religion. He did not even like to be described as passionate, for example, because he thought the world had religious connotations. For me, some of this was over-the-top, and I think it would be wiser to live and let live. He gave no quarter to me or anyone else and sometimes tempers frayed, but we never fell out and I always felt he was on the side of the angels.

We became especially good friends after we met a decade later at Florida State University, in Tallahassee. He had taken up a post there, enabling him to combine research with his educational initiatives, having retired from the University of Sussex. He and his wife Margaret lived in Tallahassee for most of the year, returning to Europe during the summer, when it is generally too hot for most English people to endure. I was researching my biography of Paul Dirac, who also retired there, and was making extensive use of his archive, which his wife had moved there from its original location in Cambridge.

I was happy that the Krotos took pleasure in my Dirac biography, The Strangest Man, which I heard Margaret read to Harry in bed at night. They even took it upon themselves to recommend the book to many acquaintances and friends, including the actor Ian McKellen. ‘We had appeared in the same production of ‘Henry V’, he told me. Ian acted everyone else off the stage even then, even when he was standing still, doing nothing’. In the summer of 2007, Harry, Margaret and Ian got together in Stratford-upon-Avon for a reunion after a matinee performance of ‘King Lear’, in which Ian was starring.

I visited Tallahassee many time in the 00s, and always looked forward to seeing Harry and Margaret, who were an extremely popular couple in the FSU community. I thought they would be there for another two decades, and was shocked to hear in February last year that he had a neurodegenerative condition that gave him and Margaret no choice but to return to England, pronto.

I last saw Harry nine days before he died, at a hospice just outside Lewes in East Sussex. He was very frail, but was made comfortable by Margaret, his family and the nurses. He was gracious enough to ask about progress on my next book. We also talked about a recent art exhibition I had seen, ‘Painting the Modern Garden’, and I gave him a copy of the catalogue. He still had the energy to mount another attack on some of his favourite bêtes noirs, including the concept of the multiverse, and the current threat of religious extremism. He was joking to the end: when a nurse poke her head round the door and breezily asked him if he needed anything, he shot back ‘How about a new body?’

Harry was laid to rest at Clayton Wood Natural Burial Ground, in the beautiful Sussex Downs, on 19 May, after an hour of tributes and music, including an excerpt from Mahler’s 4th symphony and a recording by Joan Baez of Mark Knopfler’s ‘Brothers in Arms’. In front of Harry’s coffin, Ian McKellen spoke briefly of his remembrances of his old friend, took a step to the right, and plunged into the character of Sir Thomas More, giving an electrifying reading of Shakespeare’s speech to anti-immigrant rioters in London (Grant them removed, and grant that this your noise). It was a bravura performance, and Harry would have loved every second of it. Half an hour later, his coffin was lowered into his grave with a model buckyball. We mourners scattered rose petals and then handfuls of soil into the open grave. Harry was at peace, his life well lived.

Obituaries of Harry

In the Daily Telegraph.

In the New York Times.

In the Guardian.